The one really nice thing about the aviation industry is there is never any pressure, right?

If you believe this statement, I have some oceanfront property in Arizona to sell you. In fact only medical and the military have more constant pressure then aviation.

The dictionary defines pressure as “the urgency of matters that require attention. Pressure is very closely related to stress (remember last month’s article) and in fact is actually stress at work.

Last month we talked about the stress curve and showed how an increase in stress can result in an increase in performance/productivity. However, if you have too much stress and go over the curve then performance/productivity can suffer. Remember its management’s job to provide you with some pressure to ensure productivity as with productivity comes profit and with profit comes your paycheque.

Knowing what you now know about pressure, where do you think most of your pressure comes from? Well, management of course! If you believe that then you are once again wrong. Studies have shown that most of our pressure comes from us followed second by peer pressure and in a distant last is management pressure.

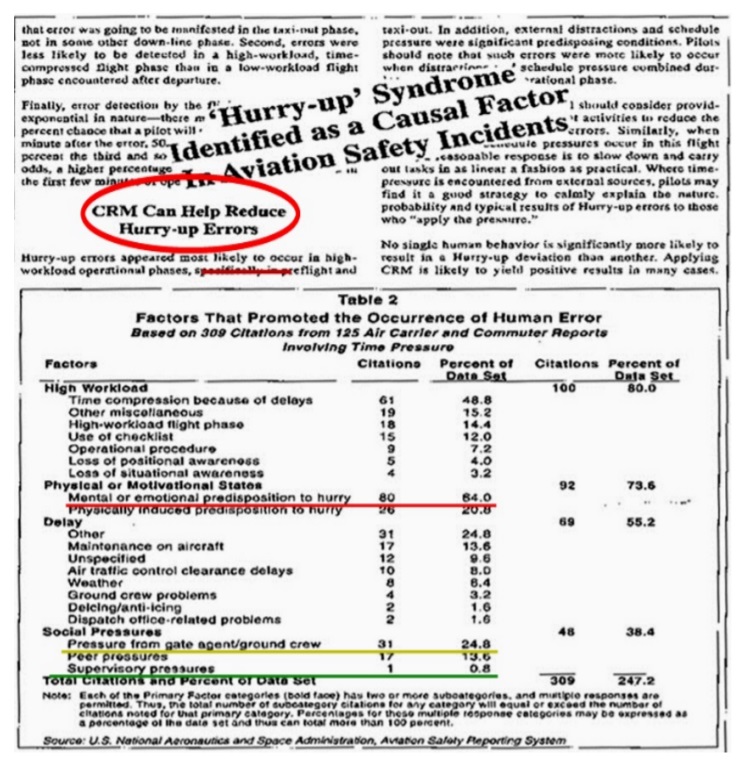

Let’s take a look at a US National Aeronautics and Space Administration study that reviewed 309 pilot citations (violations) all involving time pressure. I suspect that most of the pilots initially said that management pressure was responsible for pushing them into making human errors. Yet when you take a closer look, you will see that “supervisory pressures” were

found in only one case which puts it in at less than 1%. Peer pressure

was found in 17 cases for 13.6% and self-pressure or “mental or emotional predisposition to hurry” was the highest of all in 80 cases or 64.0%.

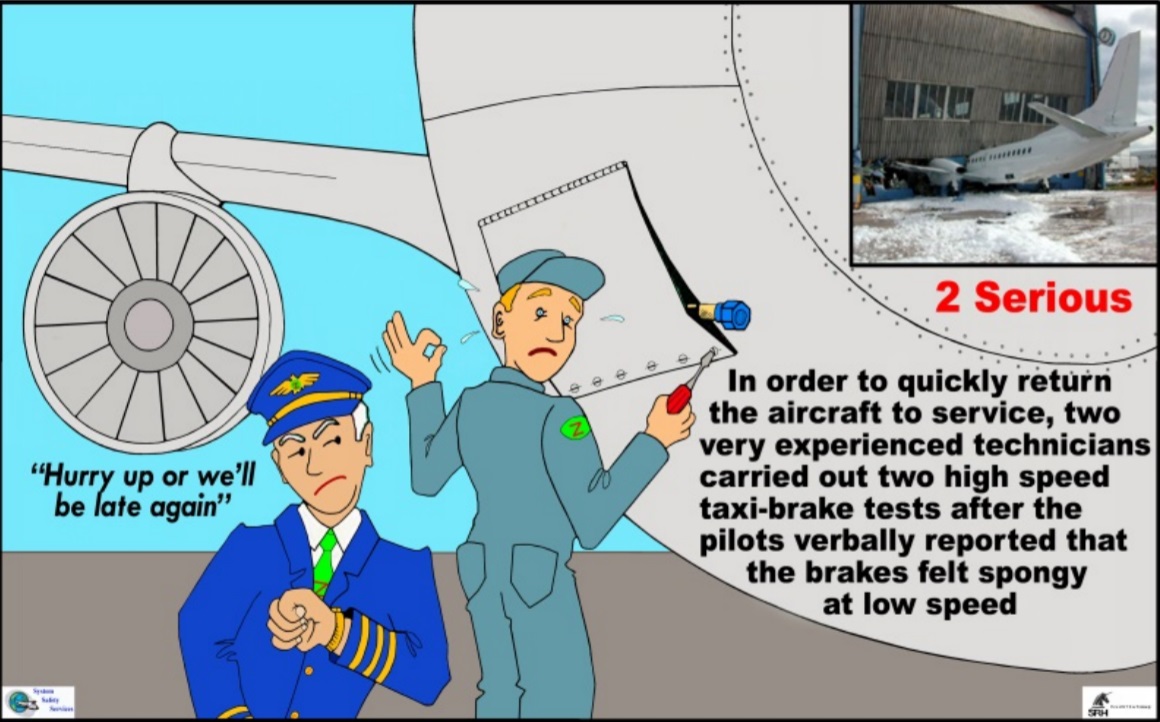

It is interesting to note that “pressure from gate agent/ground crew” was almost 25% and higher than both peer and management. Pilots are not required to obey gate agents or ground crew yet the pressure from both contributed to the errors made. Most errors were made during when a pilot had a high workload and “time compression because of delays”. In fact, 90% of the errors were made before the aircraft had even left the ground and almost 70% of the errors were from deviating from ATC, FARs or company SOPs. I suspect that likely these deviation were “short cuts’ carried out to benefit the company by saving time. A maintenance study conducted after an error would likely reveal much the same analysis results.

In my much younger days I can recall a crew chief telling me to do what you have to do but make sure you get that plane out on time. Of course he wanted the job done Safely but the top underlying priority was to take what “Safe” short cuts you had to in order to finish the job on time.

I am going to show you one of my favourite models to help you understand why management pressure is actually very low.

It’s called The Monkey Model.

It is management’s job to give you monkeys (jobs or tasks), and it’s your job to accept these monkeys if you want the banana the monkey is holding (the banana is your paycheck). Once you accept the monkey, any pressure is now yours (self-pressure). If you cannot do the job Safely then you have to speak up (Assertiveness remember) and state your Safety case and if they insist that you do the impossible, then and only then is it management pressure. However, you need to watch out for the times when the monkey turns out to be a gorilla. This occurs when the supposedly small job turns out to be a bigger one than originally expected. This tends to occur most often on a midnight shift when it is near impossible to bring in help on overtime. Let’s fact it no one wants to take the hit for a delay however taking short cuts should never be the answer.

A lot of years ago I joined a crew that had a reputation for always getting the aircraft they were responsible for out on time. They were a team that worked well together and were proud of their reputation. I recall asking what happens when there is just too much work to be done and two few maintainers to do it (the gorilla). The crew chief replied, “well sometimes we just have to defer a few things and we catch them later.” When asked just what he meant by “defer” he explained that you just skip some of the items on the layover check sheet and catch them the next night. One item that would be skipped was the checking of the 10 tires on the DC8. It was too time consuming to do and we thought, “what’s the big deal to skip it for one night?” After all, how often do you check the pressure in your car tires? We also knew that management wanted our aircraft to be the first in the lineup when the curfew came off. I said that I would not sign for anything that I had not done. No problem he replied. “You just initial MM for Mickey Mouse or DD for Donald Duck.” I asked, “does everyone do this?” The reply was “just when there is too much work and we have to get the aircraft out on time.” That was a norm that was born from pressure. At the time, I believed that it was management pressure that was condoning this illegal action but I have no idea how far up the management chain this practice was sanctioned. It is very possible that they had no idea that their “atta-boys” were encouraging this action.

There was a lot of peer pressure and as a newbie to the crew; you want to show that you are a team player. In the end, as I look back, I realize that it was selfpressure to get the job done that was the prime motivator. Had I refused to participate in this norm, there would have been no consequences.

Pressure is a way of life so what does one do when the pressure becomes excessive? This is where Mom’s advice comes into play. Always remember that Mom is never wrong. So:

STOP and assess the situation.

LOOK at the situation rationally:

- What is the reality of the situation?

- What has to be done to Safely complete the work on time?

- Have I communicated my concern in a concise and rational way?

- What is the worst that could happen?

LISTEN to the rational mind: o Has this happened before? o What was the outcome? o What is the best plan for a positive outcome?

ACT – this can be the hardest part. It may not be easy to be assertive and speak up for what is required. Be sure to have a suggested plan with a “ready time” if the plan is implemented.

When Safety comes into question, one must “draw that line in the sand” and refuse to cross it. I crossed my own line with the initials MM or DD because of pressure. Please take a few moments to read the case study of the first training video that I produced called “Death of an Airline” – www.system-safety.com Click on “Safety Videos,” “Death of an Airline” and “Case study #1 near the bottom. I could have just as easily been responsible for 261 deaths as this accident was the result of one tire having low pressure. Now that is something that no one would ever want to have to live with. The next article will conclude the Dirty Dozen articles on the contributing factors to the human error you never ever intend to make. It covers something that you may not of been aware of.