Every industry has its own culture and aviation is no different. Our industry is known as being very unforgiving for any human errors made; especially if the error involved damage to an aircraft. Giselle Richardson, a close psychologist friend of mine was the keynote speaker at our first conference on Maintenance Errors and Their Prevention in 1995. In her speech she gave us a lot to think about however, one thing she said that has stuck in my mind to this day was: “Only the mafia with their cement boots has a harsher discipline policy (than aviation)”. Thinking on my many years in aviation I believe that she was right. I can recall going to work one day and asking where Joe was. It turns out he was fired on my days off and not one person knew why. It was later rumored that he had left his flashlight up behind the instrument panel which later had fallen out on the Captains foot during pushback from the gate, resulting in a delay.

Was it “Cement boots” for Joe? Let’s look at some of the cultures that can be found in our industry:

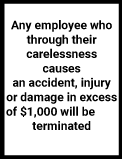

The era of the “Blame” Culture.

This culture has been very common throughout history.

It is based on the “eye for an eye” way of thinking.

It is seen to be doing something about the problem.

It seems to “solve” the problem as the instigator of the problem is no longer there to do it again.

It does not determine or solve the root causes of the problem

It does cause persons to try to hide their errors

It creates a lose-lose situation and will doom a SMS to failure

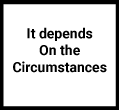

The era of the “It Depends” Culture

No one knows what will happen when an error is made

It could depend on the mood of the boss that day

It likely will depend in on how expensive the error is and how much media attention it gets

It fails to determine the root causes and results in an “It wasn’t me” culture much like the blame culture.

It is a lose-lose situation and will also doom a SMS to failure.

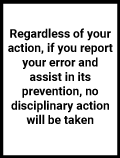

The era of the “No Blame” culture

This enables an organization to learn from the error and root causes to be found.

It lessens the chances of a repeat error being made.

The data helps find trends and system causes

However it interferes with one’s “sense of justice.” I.E. That feeling that he/she “just got away with murder.” (Came to work drunk and drove the service truck into the side of an aircraft is ok?)

It makes no provision for reckless behavior.

A “form” of this (Just Culture) is a must for a successful SMS.

What is a Just Culture?

It is where everyone feels that the “guilty party” was treated fairly and justly after they made a human error or reported a near miss.

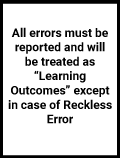

It clearly spells out that all errors will be treated as “Learning Outcomes” and except for cases of reckless behavior, no discipline will be administered.

It is a win-win situation and is the foundation of any successful SMS.

What is an Administrative Policy?

An administrative policy is one that spells out exactly how an error or reported near miss will be administrated or handled. It will inform all exactly where that “line in the sand” is when it comes to discipline. The administrating of discipline will become a small part of the overall policy.

The policy is based the following suppositions:

a) Errors are not made on purpose (if they were it would be sabotage);

b) The person making the error is the least likely to ever make it again;

c) Disciplining a person, usually does nothing positive to reduce a repeat of the error if it was not intentional;

d) The policy will become the heart of your SMS.

It has been determined that 95 to 97% of the time discipline will not be required to help prevent a repeat of the error.

Based on work done by David Marx, the father of Just Culture, the following are the three types of error that must be dealt with.

- Normal Error – No Culpability = Learning Outcome (Console)

Normal errors are the result of being human and/or the system the person is working in. It is the unintentional forgetting to do something or doing something wrong, thinking it was right. There is no intention to make the error and later may think to yourself: “How could I have been so stupid.” For example. Forget to replace the oil cap after checking the oil level. Install a component wrong because you have never had the training (system error) and the manual is ambiguous but it seems right.

The end result is a “Learning Outcome” in which the knowledge gained is used to devise ways to prevent it from occurring again to anyone.

About 80% of all errors will fall into this category.

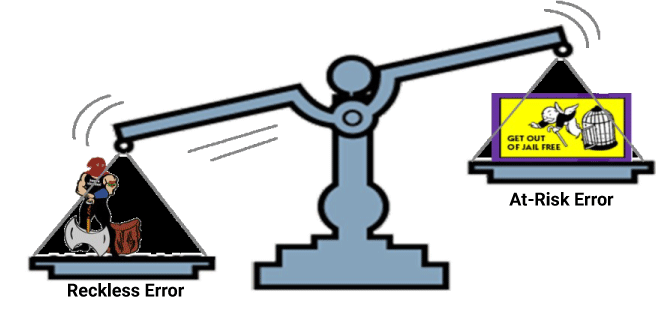

- At-Risk Error – No culpability (this time) = Learning Outcome (Coach)

At-Risk error are the result of the person knowing what he/she is doing is wrong but sees no bad outcomes and often positive rewards for the action. The key is the person fails to see or realize the risk in what they are doing. Norms (the way we do things around here) often result in an at-risk error.

Remember last month’s “Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck “pencil whipping” for the tire pressures on the DC8s? That was a norm that ultimately resulted in the loss of 261 lives. Because the persons were not aware of the risk in what they were doing they would receive one “get out of jail free” and be coached to realize the danger or risk. Should the person repeat the error when they now realize the risk, the error falls into the reckless error category.

The classic norm that was at-risk has to be American Airlines DC-10 Flight 191 out of Chicago that lost the number one engine on take-off. Two hundred and seventy three persons would die as a result of maintenance using a forklift to remove and reinstall the wing mounted engines with the pylon attached instead of separating the engine from the pylon before removing the pylon. This was an At-risk error as what they were doing was a violation but they failed to see the risk but had the positive reward of saving 22 man-hours per engine. To my knowledge, no person was ever charged (disciplined) for this At-risk error.

- Reckless Error – Culpable = Learning Outcome (Discipline)

Reckless error is the result of an action that the person knows has a significant and unjustifiable risk but chooses to do it anyway with a conscious disregard of the possible consequences. The best example of this is the drunk who chooses to drive. The person knows the risk but chooses to do it anyway. An aviation example would be the maintenance person who realizes he forgot his flashlight up behind the instrument panel and decides to say nothing. There can still be a learning outcome as to why the person chose to take that risk but discipline may be required to ensure that it does not happen again.

But how do you tell the difference?

For the answer, you will need to answer the following questions.

#1. Was the act deliberate with a reasonable knowledge of theconsequences? Yes = Reckless

#2 Has the person made similar errors in the past? Yes = Reckless

#3 Do they accept responsibility for their actions? Yes = Likely At-risk

#4 Has the person learned from the experience? Yes = Likely At Risk

#5 Are they likely to do it again? Yes = Reckless

The only purpose of discipline has to be “To Ensure that it does not happen again”.

There will be those who will have trouble agreeing with this culture change and will hide behind the “he/she must be held accountable” adage. This is the ruminants of the Blame (cement boot) culture. This is especially true of the At-risk error where the error was knowingly made but the possible consequences wern’t.

At-risk errors only occur about 15% of the time leaving Reckless errors with the outcome of discipline responsible for only 5%. Who would have ever thought it would be that low? In a true Just Culture it will be and the cement boots will be a thing of the past.